Western style baked bread is not a staple of the traditional Chinese diet, but it has been quickly catching up among China’s urban middle class during the past 20 years, in which China’s baking sector has grown by 10% annually, and bread has been the main driver product. Bread was good voor 44% of the total value of the Chinese baking industry in 2018. The value of the Chinese bread market is expected to reach RMB 266.3 billion in 2020.

According to a staff member of the bakery chain BreadTalk, 80% of their clientele were foreigners, when she started working there in 2005. This has changed completely, and now Chinese are the main customers.

A product for the young and the affluent

When you take the time to observe the activities at any bread store in a Chinese city, you can observe that at least three quarters of the regular domestic patrons are (young) professionals, white collar workers. Older people still regard bread as something that is foreign. They do not dislike it, but it is something you consume occasionally, as a snack.

Moreover, bread is still regarded as relatively expensive. Teenagers and students like to ‘hang out’ in and around bread and cake shops, because they like to cozy ambience that all chains like to create. However, they only occasionally actually buy Western style bread or pastry, because it is too expensive.

Chinese like it soft

When bread first started to come up in the mid 1980s, the preferred type was the soft, white bun, with a relatively sweet flavour. It had to be extremely soft. As one European bakery technician with whom I used to travel through China put it like this:

‘Chinese bread should be made of such a texture, that you can put it in an ordinary envelope, put a stamp on it and send it to your friend. When your friend opens the envelope, the bread should restore to its original shape’

This has started to change recently. Chinese consumers are gradually learning to appreciate more salty types of bread, bread with harder crusts, and whole grain bread.

Bread is also gaining ground in the breakfasts of more and more urban Chinese, replacing porridge, fried dough sticks (youtiao) and steamed bread (mantou).

The sandwich is starting to replace the bowl of (instant) noodles a Chinese office worker typically eats for lunch. The advantage of bread over these traditional breakfast and lunch items is time: you can buy a week’s supply of bread, while traditional breakfast and lunch need to freshly prepared.

Facts & figures

The Chinese consumed 2 mln mt of bread in 2016. That is a lot, but the per capita consumption of bread is approximately 2 kg p.a. (in the urban regions about 3.2 kg), compared to 10 kg in Japan and 9 kg in Taiwan. Insiders expect that the Chinese bread consumption will gradually rise to the level of Taiwan, which means that the growth potential is enormous.

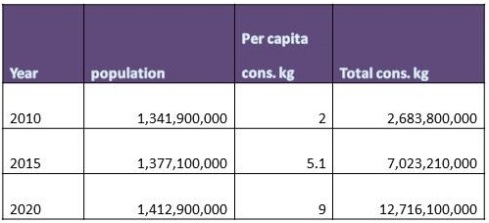

According to the above estimates, the current Chinese bread consumption already exceeds 1 million mt p.a. This would grow to 9 million mt p.a., if the population would remain the same. If we apply the Chinese estimate for the population by 2020, the Chinese bread consumption would rise to 12.5 million mt p.a. The estimated development is reflected in the following table.

Market structure

Bread is a localised business in China. There are very few regional suppliers, let alone producers that sell on a nationwide scale. It is also still a very Chinese business. Multinationals are present, but do not dominate. The largest bakery company in the world by far, Grupo Bimbo, has a very small presence in the market with just one plant.

One of the few companies with such a status is Mankattan Food Co., Ltd. Mankattan has been established by the Belgian Artal Group in 1995. Mankattan has achieved a large market share through direct distribution of bread products to retail, food service and school locations. The main company is located in Shanghai, with subsidiaries in Beijing and Guangdong, giving it production centres in China’s most densely populated regions.

Another successful example is Taoli (Toly) Bread (Shenyang, Liaoning). However, Taoli also produces traditional Chinese bakery items like mooncakes and zongzi. Still, the fact that the word ‘bread’ is part of the company indicates that it is its leading product. Taoli was listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange in December 2015. Taoli generated a turnover of RMB 2.939 billion in the first half of 2021; up 7.32%.

Worth keeping on your radar is also Ranli Food (Zhangzhou, Fujian). This producer of biscuits and pastry launched a pumpin bread in 2019. Its pumpkin content is at least 16%, creating a unique flavour and (natural) colour and considerably increasing the fibre content.

Another healthy bread newly launched in 2019 is ‘sugar-free low calorie low fat’ whole grain bread by Shanghai-based Laidalin. A blogger claims that ‘it is so light, that if feels like eating air bubbles’. I personally prefer a firmer type of bread for my early morning cheese sadwhich, but as introduced above: Chinese like it soft.

Several domestic and foreign bakery chains are gaining ground on large Chinese bakery companies like Christine and Holiland. The South Korean chain Paris Baguette now has 37 stores in China, the Taiwanese chain 85°C Bakery Cafe has about 145, the Singaporian venture BreadTalk 170, and the South Korean chain Tous les Jours 140. Starbucks Coffee is also developing in this direction in China. A good sign of the growth potential of this sector is that BreadTalk’s net profit increased 91% in 2017 to RMB 21.85 mln.

Some experienced players from Hong Kong have also expanded to the Mainland, like: Queen’s Cake Shops, Maxim’s and Aji Ichiban, which may sound Japanese, but has Chinese founders.

A common feature of all chains in this category is that they tend to be located in office buildings and high end shopping centres, close to their largest market segment.

Case study: Euro Bakery, an ambitious Dutch investor

Euro bakery, a 130 staff bakery in the Beijing region founded by Dutch investor Henny Fakkel, recently received a loan from the Netherlands Finance Development Company (FMO). The bakery is now expanding its business with a long-term EUR 2 mln loan from FMO.

Euro bakery specialises in traditional as well as new-style bread and cake variations, from European-style big loaf bread, rolls, whole wheat sourdough breads to pastry varieties, muffins and cookies, Danish pastry and also cheese savoury cookies. The bakery did well over the past years to tap into the growing popularity of bread products in China’s capital. The bakery factory of 135 staff caters for cafes like Costa coffee, Pacific coffee, and for companies like IKEA, International schools, Compass Group, Sodexo, airport catering, Pizza Express, embassies, hotels, restaurants and wholesalers.

Euro bakery has come a long way since Henny Fakkel and Grace Wang started the business in 2006. The bakery has managed to extend its large-client base to 60, and with a staff of 135, the bakery produces seven days week and distributes its products all over China via 450 delivery points.

Euro bakery wants to expand to 4000 m2 and build its own bakery education institute to train itd staff and disadvantaged young people to give them the chance to follow a baking course.

Frozen technologies

Insiders believe that the penetration of frozen technologies in baked goods will increase in the future. In China, where labour is abundant and cheap, it may be counterintuitive to see penetration of a high-end technology for production of baked goods growing. However, increasing complexity and diversity of products in industrial bakeries is driving the requirement for frozen solutions. It is already deployed in 20% of western style baked goods in the country.

In the artisanal sector, which is about 56% of the Chinese bakery industry by value, the penetration of frozen technologies is very low. The highest penetration of frozen technologies is in branded/packaged baked goods. This trend is changing and we are seeing many local and medium-sized bakery companies also interested in frozen technologies. Ingredient manufacturers should be wary not to miss these opportunities for specialist ingredients for frozen bakery products.

Key target for food ingredients

Bread is pointed out by Northern Sunlight, China’s largest distributor of food ingredients, as one of the most interesting growth markets.

This is corroborated by a the Director of the China Food Additives Association (CFAA), who claims that he regards Bakery China as the most prominent competitor of CFAA’s Food Ingredients China (FIC). Bakery China is organized annually in May, covering 9 halls of the Shanghai New International Exhibition Centre. Apart from baking products, it also covers ice-cream and pasta and all ingredients for the entire product range.

Virtually all Chinese bakers are using bread improvers, compound ready-to-use ingredients, comprising enzymes, emulsifiers and a various other additives. I have already introduced the structure of the market for flour and baking ingredients in a previous blog. You can see more details there.

Here is the ingredients list of Mankattan Coarse Grain Toast Bread:

Wholegrain wheat flour, water, HFCS, shortening, yeast, bran, salt, gluten powder, flavour, additive [bread improver (starch, vitamin C, enzymes, calcium propionate)].

The way the ‘additive’ is broken down in individual ingredients is prescribed by law. Although not stated verbatim, it indicates that the producer does not purchase those ingredients separately, but buys a ready-to-use bread improver.

Other ingredients include various shapes and textures of fruits (e.g. dates), vegetables, nuts and meat, cheese powder, yeasts, nutrients for fortification, flavours, special oils or fats, fresh butter, cream, shortening, starch and modified starch, chocolate in various presentations, dairy based ingredients, and much more.

Clean bread

Concepts like Clean Label have also reached China and started to get serious around 2022. However, the Chinese interpretation of ‘clean’ seems to be broader or lest strict than the Western. Here is an example of a clean bread from Eurasia Consult’s database that is advertised as ‘zero additives’ site in China.

Product name: nut cart wheel bread

Ingredients

Whole wheat flour, walnuts (>= 22%), water, red beans, gluten powder, bran, oligo-isomaltose, fresh milk, matcha (>= 1%), sodium coppe3 chlorophylin, yeast, sodium bicarbonate, calcium propionate.

New development: ‘2 Yuan Bakery’

Offering high earnings with little investment, bakeries selling bread (round buns, not an entire loaf) for just RMB 2 have shot up across China in 2023. Beginning September of that year, several social media posts showcased individuals who claimed to have quit their jobs to open a bakery, earning substantial incomes with low investment. For example, a young mother and a woman in her 20s claim monthly earnings of RMB 130,000 yuan – 180,000, respectively, after opening bakeries. Such outlets are often strategically placed in communities close to schools or markets in cities where rental costs are more manageable. Read more about that here.

Peter Peverelli is active in and with China since 1975 and regularly travels to the remotest corners of that vast nation. He is a co-author of a major book introducing the cultural drivers behind China’s economic success.

Pingback: Harbin – where the West meets the East | Peverelli on Chinese food and culture

Pingback: Leisure food – A very Chinese food group | Peverelli on Chinese food and culture

Pingback: Potato growing & processing in China | Peverelli on Chinese food and culture

Pingback: Discovering the Holiland . . . in China | Peverelli on Chinese food and culture

Pingback: China’s breakfast revolution | Peverelli on Chinese food and culture

Pingback: Belt and Road – Wheat and Yeast | Peverelli on Chinese food and culture

Pingback: China’s major food regions | Peverelli on Chinese food and culture

Pingback: Black is beautiful – also in food | Peverelli on Chinese food and culture

Pingback: Nothing sweeter than sweeter than sweet potato | Peverelli on Chinese food and culture

Pingback: I Love You – what Chinese do with oat | Peverelli on Chinese food and culture

Pingback: Enzyme applications in the Chinese food and beverage industry | Peverelli on Chinese food and culture

Pingback: New foods launched in China in 2015 | Peverelli on Chinese food and culture

Pingback: Discovering the Holiland . . . in China | Peverelli on Chinese food and culture

Pingback: The revival of famous food and beverage brands of the past | Peverelli on Chinese food and culture

Pingback: Train food in China | Peverelli on Chinese food and culture

Pingback: Harbin – where the West meets the East | Peverelli on Chinese food and culture

Pingback: Date (jujube) Processing in China – spotted in New Mexico | Peverelli on Chinese food and culture

Pingback: The market for flour improvers and ingredients in China | Peverelli on Chinese food and culture

Pingback: China’s top private food & beverage companies of 2019 | Peverelli on Chinese food and culture

Pingback: What on earth are . . . mantou? | Peverelli on Chinese food and culture

This is a great poost

Pingback: Uncle and Aunty Xiong, French bakers in Beijing | Peverelli on Chinese food and culture

Pingback: Demographic segmentation of the Chinese food market | Peverelli on Chinese food and culture